This week's episode of Word Machine brings together poems from two Northern California poets, with the eyes on Manhattan.

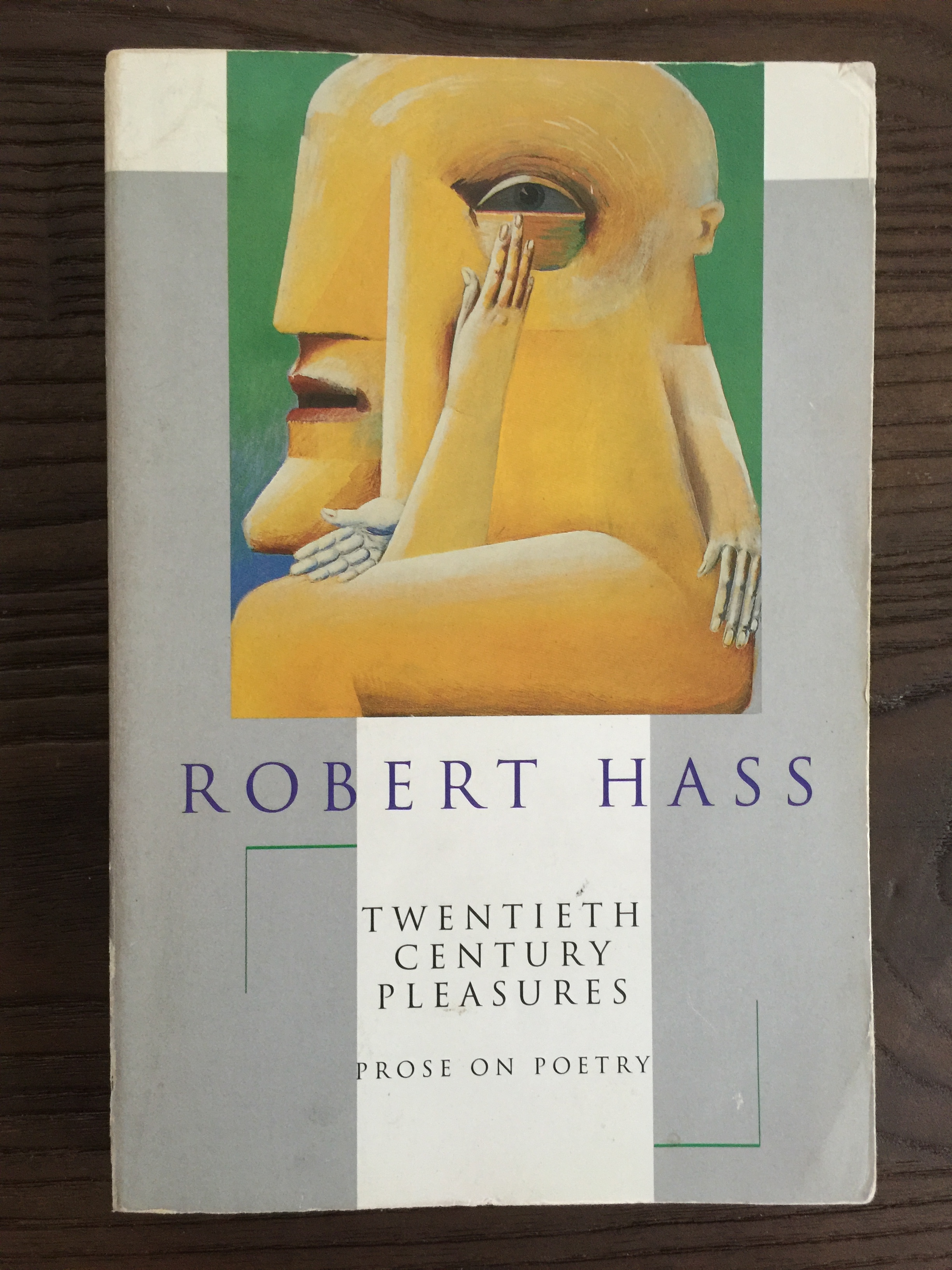

Book of the Day — Twentieth Century Pleasures by Robert Hass

The essays on poetry in this book, Twentieth Century Pleasures by former U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Hass, has been a deep well of insight, mystery, inspiration and thought for me for 15 years.

Aspen groves. Breckenridge, Colorado, USA Photo by Twenty20/Jawill529

POTD - The Problem with Describing Trees by Robert Hass

The Problem of Describing Trees

The aspen glitters in the wind

And that delights us.

The leaf flutters, turning,

Because that motion in the heat of August

Protects its cells from drying out. Likewise the leaf

Of the cottonwood.

The gene pool threw up a wobbly stem

And the tree danced. No.

The tree capitalized.

No. There are limits to saying,

In language, what the tree did.

It is good sometimes for poetry to disenchant us.

Dance with me, dancer. Oh, I will.

Mountains, sky,

The aspen doing something in the wind.

POTD - Vintage by Robert Hass

VINTAGE

They had agreed, walking into the delicatessen on Sixth Avenue, that their friends’ affairs were focused and saddened by massive projection;

movie screens in their childhood were immense, and someone had

proposed that need was unlovable.

The delicatessen had a chicken salad with chunks of cooked chicken in a creamy basil mayonnaise a shade lighter than the Coast Range in August; it was gray outside, February.

Eating with plastic forks, walking and talking in the sleety afternoon, they passed a house where Djuna Barnes was still, reportedly, making sentences.

Bashō said: avoid adjectives of scale, you will love the world more and desire it less.

And there were other propositions

to consider: childhood, VistaVision, a pair of wet, mobile lips on the screen at least eight feet long.

On the corner a blind man with one leg was selling pencils. He must have received a disability check,

but it didn’t feed his hunger for public agony, and he sat on the sidewalk slack-jawed, with a tin cup, his face and opaque eyes turned upward in a look of blind, questing pathos—

half Job, half mole.

Would the good Christ of Manhattan have restored his sight and two thirds of his left leg? Or would he

have healed his heart and left him there in a mutilated body? And what would that peace feel like?

It makes you want, at this point, a quick cut, or a reaction shot. “The taxis rivered up Sixth Avenue.” “A little sunlight touched the steeple of the First Magyar Reform Church.”

In fact, the clerk in the liquor store was appalled. “No, no,” he said, “that cabernet can’t be drunk for another five years.”

My 5 - Portable Poetry Library - Ryan Nance

Most of my poetry library ( a library I've been very proud of) is in storage, or has been traded, gifted or lost. I've dragged it around the world with me, in cardboard boxes, plastic bins, bags. It's grown. There was a period before I first left for study in Madrid where I thought about winnowing it to the essentials. I would after all not be able to read it all, even given the chance. I ended up adding to it: new books by some of my favorite poets, old books by poets I'd never heard of. It was and is a joy to find, remember and discover new works. Like stumbling upon a neighborhood I'd never once been to before. Delicious. Full of possibility. In this period I was adding young poets ( Ben Lerner, Matthea Harvey, Tracey K. Smith [whose Life on Mars just won the Pulitzer], Christine Hume ), classmates (Gabrielle Calvocoressi, Tom Healy and Ravi Shankar),

The Great Reduction

For a lot of reasons, having a large library, even of slim, tidy volumes, became impossible for me. Storage, display, space, time. I've reduced my library down to the ones I read. Seems a bit self-fulfilling, I know. But, I am often asked (and overwhelmed by the possibilities) for the books and poets I'd recommend people start with. This great filtering reduction of mine has made it abundantly clear.

So here are My 5 Portable Poetry Library

1 - Louise Glück

I haven't always been clear that I got much from her work. It was hard for me, with my life as my only computational material, to access her charged, urgent, masterful poetry. But their phrases and imagery, premises and tropes, have installed themselves as part of my psyche. I refer often to a line or image, find myself recommending. And have made sure that her books have continued to elude the great reduction.

If you haven't read her before I'd say that First Four Books of Poems is a good place to start. You'll find some of the more well-known poems ( Mock Orange, All Hallows).

Her Pulitzer Prize Winning Wild Iris and her A Village Life both offer a vast country of tight, smart, surprising poems.

2 - Donald Revell

Revell was a poet I first read while an undergraduate. I had had a very different expectation of what poetry could be before this period in my reading. When I was asked to respond to a poem for my grad school application, it was The Psalmist from The New Dark Ages that I wrote on. And now, 15 years later, I find poems of his I'd never met before and am relieved to find that the interest and power I'd felt then hasn't worn off. His books have also managed to find a place in my bags and suitcases as my library shrank.

3 - Rainer Maria Rilke

There are a few things (books, songs, paintings, places, tidbits of knowledge) that seem to contain immense and irreducible truth in something which fits into our human scale. Rilke's 3rd Elegy from his Duino Elegies has always been one of those mysteries. I've read it to people when I am ready to sound silly in my enthusiasms. I read it and its bookmates (all phenomenal poems) over and over again. On the very first meeting of grad school first-year workshop, I was asked to name a poet I cherished and explain why it was that one that I chose. I cheated. I chose two. Robert Hass (coming up) because he helped me be a better poet and Rilke because he helped me be a better person. I heard snickers at my nearly religious reverence for these two from my classmates. Rilke never has rewarded my admiration with quotables. In fact, I realize exactly how remarkable his work with the distance I feel it is from normal speech. It isn't the sort of thing you can even try to explain to people without sounding a little kookie. So, instead of explaining, I'll hope to be able to indulge in Rilke talk with more and more people soon.

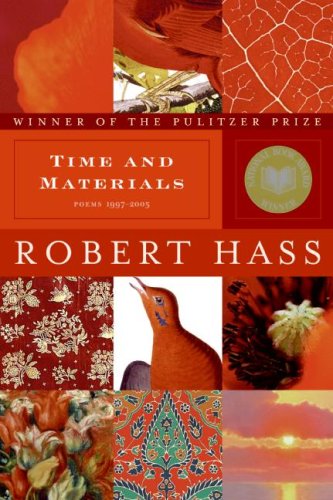

4 - Robert Hass

I have been prepared with a clear, emphatic answer to the often asked question: Who's your favorite poet? Robert Hass.

His works have been a consistent companion throughout my entire adult life. He has been the author of the words that soothed some of the worst hurts I've ever had to endure; the mind that has inspired the wonder and curiosity of mine that I have become so proud of, helped me formulate so much of my own framework for approaching the world.

His poems are the poems I've read and shared, memorized and given. All 5 of his books have and will survive any poetry reduction. I have bought 5 copies of Field Guide because I keep giving it away and then needing my own copy again.

5 - Mary Oliver

Oliver's work and words are alive with wisdom, energy and balm. I have had to keep her books around because I have needed them. And there is such reassurance that she has such an enormously large body of work, an inexhaustible fountain of some of my very favorite poetry.

my 5 is a series brought to us from the incredibly interesting readers/friends. If you have a point of view that you want to share in your own my 5, drop us a line.

I was made to think of this poem by today's post: Moving Endangered Ecuadorian Frog Portraits by Peter Lipton

POTD - On the Coast Near Sausalito by Robert Hass former Poet Laureate

On the Coast Near Sausalito

by Robert Hass

1.

I won’t say much for the sea,

except that it was, almost,

the color of sour milk.

The sun in that clear

unmenacing sky was low,

angled off the gray fissure of the cliffs,

hills dark green with manzanita.

Low tide: slimed rocks

mottled brown and thick with kelp

merged with the gray stone

of the breakwater, sliding off

to antediluvian depths.

The old story: here filthy life begins.

2.

Fish-

ing, as Melville said,

“to purge the spleen,”

to put to task my clumsy hands

my hands that bruise by

not touching

pluck the legs from a prawn,

peel the shell off,

and curl the body twice about a hook.

3.

The cabezone is not highly regarded

by fishermen, except Italians

who have the grace

to fry the pale, almost bluish flesh

in olive oil with a sprig

of fresh rosemary.

The cabezone, an ugly atavistic fish,

as old as the coastal shelf

it feeds upon

has fins of duck’s-web thickness,

resembles a prehistoric toad,

and is delicately sweet.

Catching one, the fierce quiver of surprise

and the line’s tension

are a recognition.

4.

But it’s strange to kill

for the sudden feel of life.

The danger is

to moralize

that strangeness.

Holding the spiny monster in my hands

his bulging purple eyes

were eyes and the sun was

almost tangent to the planet

on our uneasy coast.

Creature and creatures,

we stared down centuries.

Hass' clear human voice, full of curiosity and attentiveness, has always been a deep source of inspiration for me. This poem from his first collection was one of the first of his I began to connect with in that way.

POTD - Letter to a Poet by Robert Hass

Letter to a Poet

A mockingbird leans

from the walnut, bellies,

riffling white, accomplishes

his perch upon the eaves.

I witnessed this act of grace

in blind California

in the January sun

where families bicycle on Saturday

and the mother with high cheekbones

and coffee-colored iridescent

hair curses her child

in the language of Pushkin–

John, I am dull from

thinking of your pain,

this mimic world

which make us stupid

with the totem griefs

we hope will give us

power to look at trees,

at stones, one brute to another

like poems on a page.

What can I say, my friend?

There are tricks of animal grace,

poems in the mind

we survive on. It isn’t much.

You are 4,000 miles away &

this world did not invite us.

Hass has always been perhaps the poet I reach to first. This poem, in fact, was one I had my students in the Taiwanese Girls High School memorize. A year after that class finished I returned and a lot of the students ran up to me and recited it back to me.

More Poems of the Day

Gift Guides

POTD - Faint Music by Robert Hass

Faint Music

by Robert Hass

Maybe you need to write a poem about grace.

When everything broken is broken,

and everything dead is dead,

and the hero has looked into the mirror with complete contempt,

and the heroine has studied her face and its defects

remorselessly, and the pain they thought might,

as a token of their earnestness, release them from themselves

has lost its novelty and not released them,

and they have begun to think, kindly and distantly,

watching the others go about their days—

likes and dislikes, reasons, habits, fears—

that self-love is the one weedy stalk

of every human blossoming, and understood,

therefore, why they had been, all their lives,

in such a fury to defend it, and that no one—

except some almost inconceivable saint in his pool

of poverty and silence—can escape this violent, automatic

life’s companion ever, maybe then, ordinary light,

faint music under things, a hovering like grace appears.

As in the story a friend told once about the time

he tried to kill himself. His girl had left him.

Bees in the heart, then scorpions, maggots, and then ash.

He climbed onto the jumping girder of the bridge,

the bay side, a blue, lucid afternoon.

And in the salt air he thought about the word “seafood,”

that there was something faintly ridiculous about it.

No one said “landfood.” He thought it was degrading to the rainbow perch

he’d reeled in gleaming from the cliffs, the black rockbass,

scales like polished carbon, in beds of kelp

along the coast—and he realized that the reason for the word

was crabs, or mussels, clams. Otherwise

the restaurants could just put “fish” up on their signs,

and when he woke—he’d slept for hours, curled up

on the girder like a child—the sun was going down

and he felt a little better, and afraid. He put on the jacket

he’d used for a pillow, climbed over the railing

carefully, and drove home to an empty house.

There was a pair of her lemon yellow panties

hanging on a doorknob. He studied them. Much-washed.

A faint russet in the crotch that made him sick

with rage and grief. He knew more or less

where she was. A flat somewhere on Russian Hill.

They’d have just finished making love. She’d have tears

in her eyes and touch his jawbone gratefully. “God,”

she’d say, “you are so good for me.” Winking lights,

a foggy view downhill toward the harbor and the bay.

“You’re sad,” he’d say. “Yes.” “Thinking about Nick?”

“Yes,” she’d say and cry. “I tried so hard,” sobbing now,

“I really tried so hard.” And then he’d hold her for a while—

Guatemalan weavings from his fieldwork on the wall—

and then they’d fuck again, and she would cry some more,

and go to sleep.

And he, he would play that scene

once only, once and a half, and tell himself

that he was going to carry it for a very long time

and that there was nothing he could do

but carry it. He went out onto the porch, and listened

to the forest in the summer dark, madrone bark

cracking and curling as the cold came up.

It’s not the story though, not the friend

leaning toward you, saying “And then I realized—,”

which is the part of stories one never quite believes.

I had the idea that the world’s so full of pain

it must sometimes make a kind of singing.

And that the sequence helps, as much as order helps—

First an ego, and then pain, and then the singing.