VINTAGE

They had agreed, walking into the delicatessen on Sixth Avenue, that their friends’ affairs were focused and saddened by massive projection;

movie screens in their childhood were immense, and someone had

proposed that need was unlovable.

The delicatessen had a chicken salad with chunks of cooked chicken in a creamy basil mayonnaise a shade lighter than the Coast Range in August; it was gray outside, February.

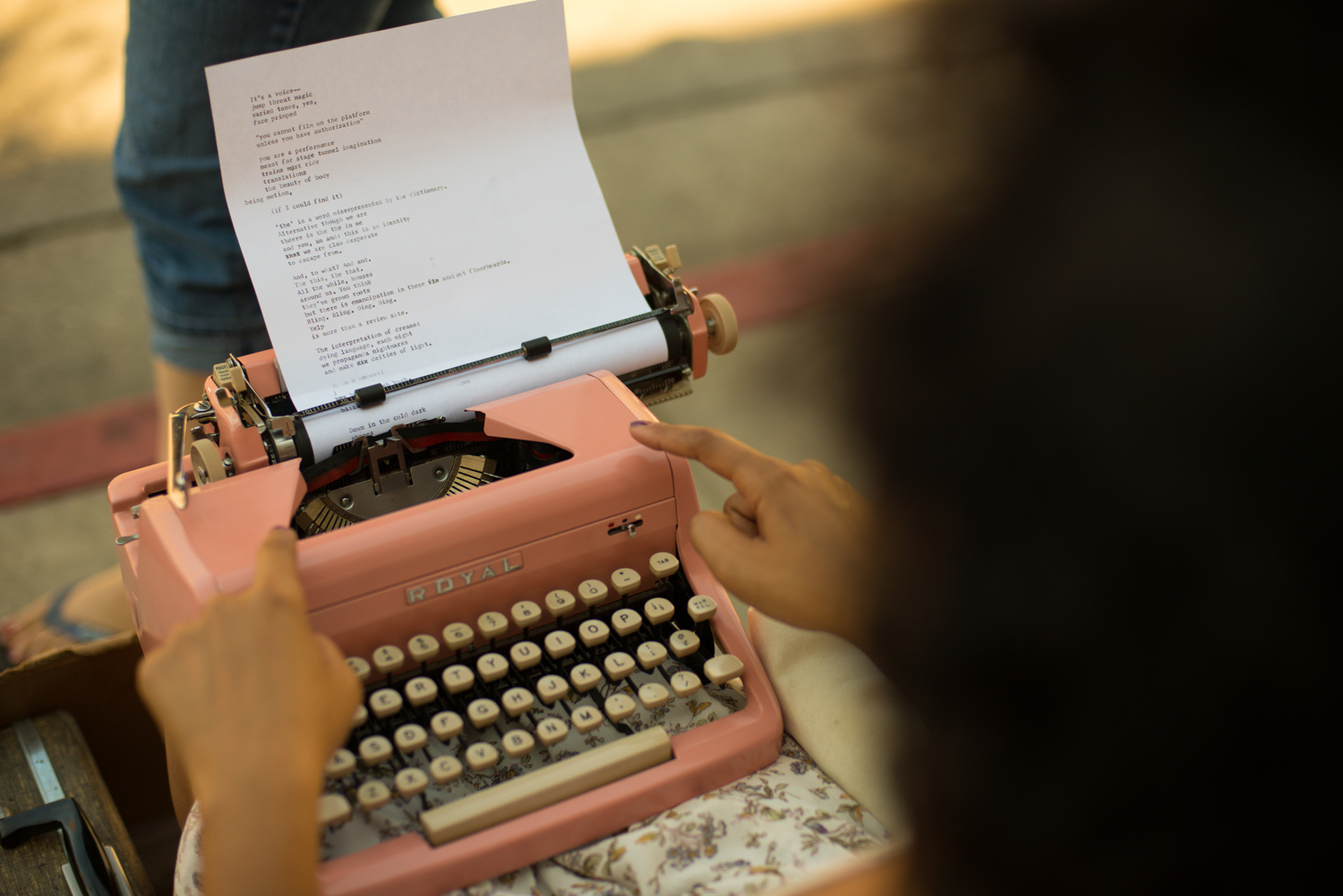

Eating with plastic forks, walking and talking in the sleety afternoon, they passed a house where Djuna Barnes was still, reportedly, making sentences.

Bashō said: avoid adjectives of scale, you will love the world more and desire it less.

And there were other propositions

to consider: childhood, VistaVision, a pair of wet, mobile lips on the screen at least eight feet long.

On the corner a blind man with one leg was selling pencils. He must have received a disability check,

but it didn’t feed his hunger for public agony, and he sat on the sidewalk slack-jawed, with a tin cup, his face and opaque eyes turned upward in a look of blind, questing pathos—

half Job, half mole.

Would the good Christ of Manhattan have restored his sight and two thirds of his left leg? Or would he

have healed his heart and left him there in a mutilated body? And what would that peace feel like?

It makes you want, at this point, a quick cut, or a reaction shot. “The taxis rivered up Sixth Avenue.” “A little sunlight touched the steeple of the First Magyar Reform Church.”

In fact, the clerk in the liquor store was appalled. “No, no,” he said, “that cabernet can’t be drunk for another five years.”